By clicking “Accept All Cookies”, you agree to the storing of cookies on your device to enhance site navigation, analyze site usage, and assist in our marketing efforts. View our Privacy Policy for more information.

[T]he kind of thinking we are, at last, beginning to do about how to change the goals of human domination … is a shift from yang to yin, and so involves acceptance of impermanence and imperfection, a patience with uncertainty and the makeshift, a friendship with water, darkness, and the earth.”

― Ursula Le Guin

One constant challenge we face in our work, be it ending violence, seeking justice for impunity, or protecting the environment, is our reliance on those in power to eventually change. That often means all our energy is spent on the dismantling side of things. This in turn means we rarely invest enough resources towards the creation process. Or if we do, the change we seek is done without the full understanding of the broader context, other movements or struggles, and so has little impact.

So we may eventually run out of steam and decide to step away from the work entirely by putting our energy into creating something new, possibly utopian, outside the system. While that may, at times, be necessary to rest, heal, recharge - if our point is to no longer engage, how useful is it to society at large? And crucially, starting from scratch often means we ignore the knowledge of what was there before, are we not at risk of repeating the same mistakes?

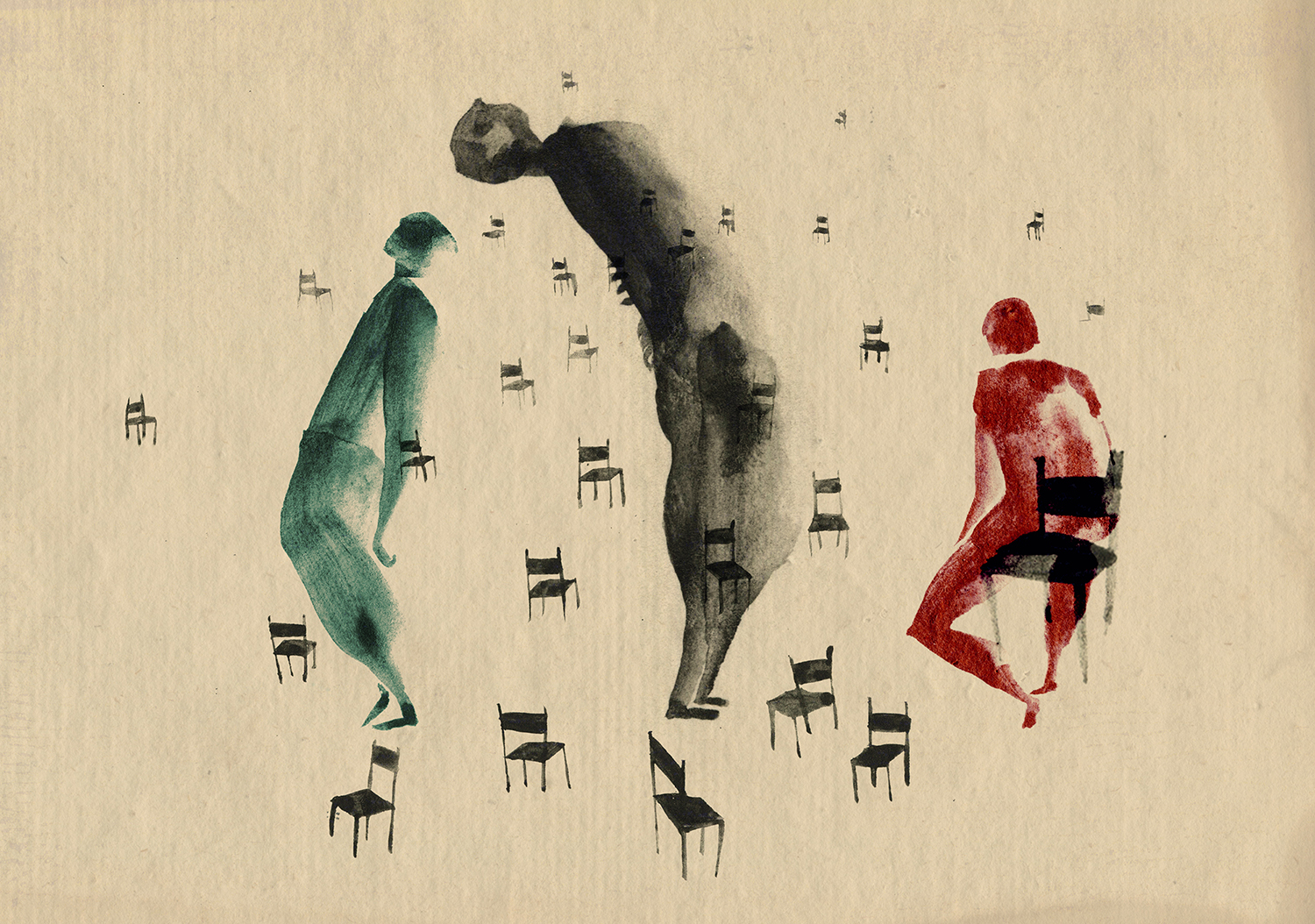

In last week’s post we wrote about utopia as a journey. Here, we want to explore how these same ideas might inspire us to build a utopia where we already stand, through disruption, subversion, or creative collaboration. This is utopia as a garden.

Gardens are both physical spaces we create and an inner sanctuary we imagine. It is both hard work and provides a safe place for our consciousness to grow.

A garden is born from careful intimate work from our hands with the earth. We must nurture it, remove certain things to make space for new ones, sow seeds, nourish, water, pick fruits.

Gardens express fusion, secrets, variability, possibility; an exchange between us and the atmosphere. In return, gardens offer us food, herbs, smells, colours, shapes, singing birds and buzzing insects. They allow us to become part of nature again.

Crucially, we must accept that we will never have complete control. So we learn to listen to the needs of the garden, understand its history, its cycles, what was there before, what must be preserved, what can be removed.

Gardens are also a symbol of our inner life; an ideal we aspire to. In most traditions and religions they represent something sacred, hidden, idealistic - they contain our imagination. Think about the garden of Eden, the Hanging Gardens of Babylon; we may each have our very own imaginary garden.

If we’re lucky, gardens are made available as a public good, with different traditions assigning gardens different purposes. Japanese gardens invite wandering and contemplation, Zen gardens may express the path to enlightenment, English gardens aim to make you feel grounded.

Building gardens also represent community and inclusion and are often used as a way to bring people together. In some instances, it’s a form of activism, as seen in the guerilla gardening movement around the world where people plant greenery in disused plots in urban settings.

Knowledge of gardening and working with nature was once handed down through generations and communities. But beyond visiting them, many of us no longer have that connection to, or knowledge of, gardens - real or imagined.

One consequence of this is that we see forms of gardens or gardening that are more of an expression of man’s domination over nature, not a search for harmony, like using pesticides to kill weeds.

Similarly, many of us no longer know how we can effectively contribute to improving society for everyone. We have forgotten the work of our ancestors, we no longer take the time to understand why something is as it is, we cannot see what should be preserved. We push against, try to control, seek quick explanations and quick solutions.

Yet beautiful things can grow from and amidst horrors or inefficiency, and the more these grow, the less power the horrors will have, and the more the inefficient will become redundant.

So how can we understand what needs to be preserved? What is the work that needs to be done to recover and restore this knowledge?

Words, Veronica Yates and illustration, Miriam Sugranyes

“Rest pushes back and disrupts a system that views human bodies as a tool for production and labour. It is a counter narrative. We know that we are not machines. We are divine.” — Tricia Hersey

“The hour is late. But the victory of tyranny over justice is not inevitable. This is our 1930s moment. Read history. Find courage. Resist this.” — Craig Mokhiber

“I believe that he who hates is destroying himself.” — Jorge Luis Borges

"A map of the world that does not include Utopia is not even worth glancing at, for it leaves out the one country at which Humanity is always landing. And when Humanity lands there, it looks out, and, seeing a better country, sets sail." ― Oscar Wilde

“I have met with but one or two persons in the course of my life who understood the art of Walking.” — Henry David Thoreau

“The human interactions with trees and the forest are deeply embedded in our collective unconscious and cultural narratives, providing many of the fundamentals of our belief systems, folklore and endlessly inspiring literature and art.” — John Tebbs